Site /

Prefatory Note Uniform Public Expression Protection Act

UPEPA00 Prefatory PrefatoryPublicExpressionProtectionAntiSLAPP

Prefatory Note

Prefatory Note ¶ 1. Special Thanks.

The Committee wishes to thank Thomas R. Burke, Stanley W. Lamport, Ben Sheffner, and Ashley H. Verdon, all of whom served as Observers during the drafting process, for their steady and valued input and expertise.

Prefatory Note ¶ 2. Introduction.

In the late 1980s, commentators began observing that the civil litigation system was increasingly being used in an illegitimate way: not to seek redress or relief for harm or to vindicate one's legal rights, but rather to silence or intimidate citizens by subjecting them to costly and lengthy litigation. These kinds of abusive lawsuits are particularly troublesome when defendants find themselves targeted for exercising their constitutional rights to publish and speak freely, petition the government, and associate with others. Commentators dubbed these kinds of civil actions "Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation," or SLAPPs.

Prefatory Note ¶ 3.

SLAPPs defy simple definition.

They can be brought by and against individuals, corporate entities, or government officials across all points of the political or social spectrum.

They can address a wide variety of issues — from zoning, to the environment, to politics, to education.

They are often cloaked as otherwise standard claims of defamation, civil conspiracy, tortious interference, nuisance, and invasion of privacy, just to name a few.

But for all the ways in which SLAPPs may clothe themselves, their unifying features make them a dangerous force: Their purpose is to ensnare their targets in costly litigation that chills society from engaging in constitutionally protected activity.

Prefatory Note ¶ 4. Anti-SLAPP Laws in the United States.

To limit the detrimental effects SLAPPs can have, 32 states, as well as the District of Columbia and the Territory of Guam, have enacted laws to both assist defendants in seeking dismissal and to deter vexatious litigants from bringing such suits in the first place.

An Anti-SLAPP law, at its core, is one by which a legislature imposes external change upon judicial procedure, in implicit recognition that the judiciary has not itself modified its own procedures to deal with this specific brand of abusive litigation.

Although procedural in operation, these laws protect substantive rights, and therefore have substantive effects.

So, it should not be surprising that each of the 34 legislative enactments have been performed statutorily—none are achieved through civil-procedure rules.

The states that have passed anti-SLAPP legislation, in one form or another, are:

Arizona (2006) (Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 12-752) (2006)

Arkansas (2005) (Ark. Code Ann. § 16-63-501 through § 16-63-508) (2005) California (1992) (Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16 through § 425.18) Colorado (2019) (Col. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-20-1101)

Connecticut (2018) (Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 52-196a)

Delaware (1992) (Del. Code Ann. tit. 10, § 8136, through § 8138) District of Columbia (2012) (D.C. Code § 16-5501 through § 16-5505) Florida (2004, 2000) (Fla. Stat. Ann. §§ 720.304, 768.295)

Georgia (1996) (Ga. Code. Ann. § 9-11-11.1)

Guam (1998) (Guam Code Ann. tit. 7, § 17101 through § 17109)

Hawaii (2002) (Haw. Rev. Stat. § 634F-1 through § 634F-4) Illinois (2007) (735 Ill. Comp. Stat. 110/15 through 110/99) Indiana (1998) (Ind. Code § 34-7-7-1 through § 34-7-7-10) Kansas (2016) (Kan. Stat. Ann § 60-5320)

Louisiana (1999) (La. Code Civ. Proc. Ann. art. 971) Maine (1995) (Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 556)

Maryland (2004) (Md. Code Ann., Cts. & Jud. Proc. § 5-807) Massachusetts (1994) (Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 231, §59H)

Minnesota (1994) (Minn. Stat. § 554.01 through § 554.06) (Held unconstitutional by Leiendecker v. Asian Women United of Minnesota, 895 N.W.2d 623, 635-37 (Minn. 2017))

Missouri (2004) (Mo. Rev. Stat. § 537.528)

Nebraska (1994) (Neb. Rev. Stat. § 25-21,243 through § 25-21,246) Nevada (1997) (Nev. Rev. Stat. § 41.635 through 41.670)

New Mexico (2001) (N.M. Stat. § 38-2-9.1 through § 38-2-9.2) New York (1992) (NY. Civ. Rights Law § 70-a and § 76-a) Oklahoma (2014) (Okla. Stat. tit. 12, § 1430 through § 1440) Oregon (2001) (Or. Rev. Stat. § 31.150 through § 31.155)

Pennsylvania (2000) (27 Pa. Consol. Stat. § 8301 through § 8305, and § 7707) Rhode Island (1993) (R.I. Gen. Laws § 9-33-1 through § 9-33-4)

Tennessee (2019, 1997) (Tenn. Code. Ann. § 20-17-101 through § 20-17-110; § 4-21-

1001 through § 4-21-1004)

Texas (2011) (Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 27.001 through § 27.011) Utah (2008) (Utah Code § 78B-6-1401 through § 78B-6-1405) Vermont (2005) (Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 12 § 1041)

Virginia (2007) (Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-223.2)

Washington (2010, 1989) (Wash. Rev. Code § 4.24.500 through § 4.24.525) (Held unconstitutional by Davis v. Cox, 351 P.3d 862, 875 (Wash. 2015))

Prefatory Note ¶ 5.

Many early anti-SLAPP statutes were narrowly drawn by limiting their use to particular types of parties or cases—for example, to lawsuits brought by public applicants or permittees, or to lawsuits brought against defendants speaking in a particular forum or on a particular topic.

Prefatory Note ¶ 6.

More recently, however, legislatures have recognized that narrow anti-SLAPP laws are ineffectual in curbing the many forms of abusive litigation that SLAPPs can take.

To that end, most modern statutory enactments have been broad with respect to the parties that may use the acts and the kinds of cases to which the acts apply.

Prefatory Note ¶ 7.

The recent trend further evidences a shift toward statutes that achieve their goals by generally employing at least five mechanisms:

1. Creating specific vehicles for filing motions to dismiss or strike early in the litigation process;

2. Requiring the expedited hearing of these motions, coupled with a stay or limitation of discovery until after they're heard;

3. Requiring the plaintiff to demonstrate the case has some degree of merit;

4. Imposing cost-shifting sanctions that award attorney's fees and other costs when the plaintiff is unable to carry its burden; and

5. Allowing for an interlocutory appeal of a decision to deny the defendant's motion.

Prefatory Note ¶ 8. The Need for a Uniform Anti-SLAPP Act.

Although there is certainly a movement toward broad statutes that utilize the five tools described above, the precise ways in which different states have constructed their laws are far from cohesive.

This degree of variance from state to state—and an absence of protection in 18 states—leads to confusion and disorder among plaintiffs, defendants, and courts.

It also contributes to what can be called "litigation tourism"; that is, a type of forum shopping by which a plaintiff who has choices among the states in which to bring a lawsuit will do so in a state that lacks strong and clear anti-SLAPP protections.

Prefatory Note ¶ 9.

Several recent high-profile examples of this type of forum shopping have made the need for uniformity all the more evident.

Prefatory Note ¶ 10.

The Uniform Public Expression Protection Act seeks to harmonize these varying approaches by enunciating a clear process through which SLAPPs can be challenged and their merits fairly evaluated in an expedited manner.

In doing so, the Act actually serves two purposes: protecting individuals' rights to petition and speak freely on issues of public interest while, at the same time, protecting the rights of people and entities to file meritorious lawsuits for real injuries.

Prefatory Note ¶ 11. The Uniform Public Expression Protection Act, Generally.

The Uniform Public Expression Protection Act follows the recent trend of state legislatures to enact broad statutory protections for its citizens.

It does so by utilizing all five of the tools mentioned above in a motion practice that carefully and clearly identifies particular burdens for each party to meet at particular phases in the motion's procedure.

Prefatory Note ¶ 12.

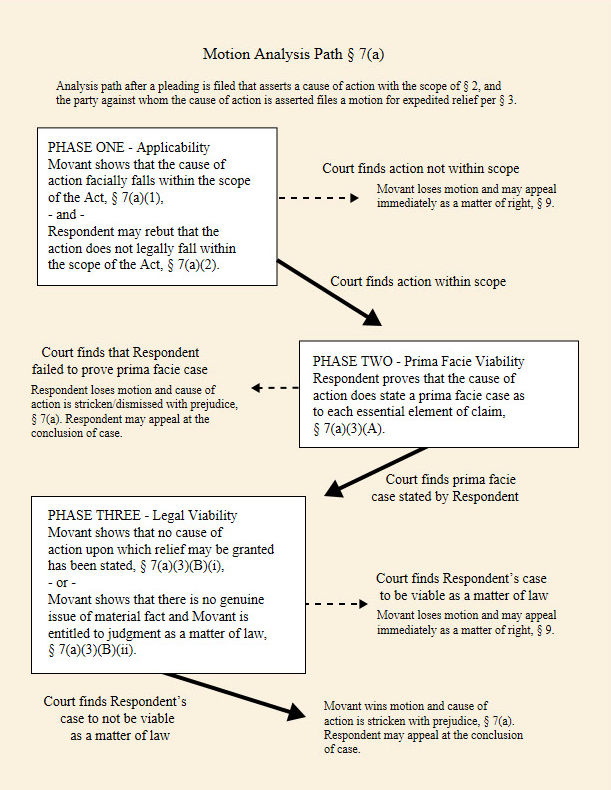

The general flow of a motion under the Act employs a three-phase analysis seen in many states' statutes.

Upon the filing of a motion, all proceedings — including discovery — between the moving party and responding party are stayed, subject to a few specific exceptions.

In the first phase, the court effectively decides whether the Act applies.

It does so by first determining if the responding party's (typically the plaintiff's) cause of action implicates the moving party's (typically the defendant's) right to free speech, petition, or association.

The burden is on the moving party to make the initial showing that the Act applies.

If the court holds that the moving party has not carried that burden, then the motion is denied, the stay of proceedings is lifted, and the parties proceed to litigate the merits of the case (subject to the ability of the moving party to interlocutorily appeal the motion's denial).

If the court determines that the moving party has carried its burden, then the responding party can show its cause of action fits within one of the three exceptions to the Act.

If it carries that burden—for example, by showing that its cause of action is against an agent of a governmental unit acting or purporting to act in an official capacity—then the Act does not apply, and the motion is denied.

If it fails to carry that burden, then the court proceeds to the second step of the analysis.

Prefatory Note ¶ 13.

In the second phase, the court determines if the responding party has a viable cause of action from a prima-facie perspective.

In this phase, the burden is on the responding party to establish a prima-facie case for each essential element of the cause of action challenged by the motion.

If the court holds that the responding party has not carried its burden to establish a prima-facie case, then the motion is granted, and the responding party's cause of action is terminated with prejudice to refiling.

The moving party is entitled to its costs, attorney's fees, and expenses.

If the court holds that the responding party has carried its burden, then—and only then—the court proceeds to the third step of the analysis.

Prefatory Note ¶ 14.

In the third phase, the court determines if the responding party has a legally viable cause of action.

In this phase, the burden shifts back to the moving party to show either that the responding party failed to state a cause of action upon which relief can be granted (for example, a claim that is barred by res judicata, or preempted by some other law), or that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law (for example, if the cause of action, while perhaps factually viable, is time-barred by limitations).

If the moving party makes such a showing, the motion is granted; if it fails to make such a showing, the motion is denied.

ARTICLES

- 2015.8.29 ... A Call For A Uniform Anti-SLAPP Act

PREFATORY NOTE OPINIONS