Site /

Dismissal Striking Uniform Public Expression Protection Act

UPEPA07 Dismissal DismissalStrikingPublicExpressionProtectionAntiSLAPP

SECTION 7. [DISMISSAL OF] [STRIKING] CAUSE OF ACTION IN WHOLE OR PART.

(Without Commentary — With Commentary Interlineated Is Below)

(a) In ruling on a motion under Section 3, the court shall [dismiss] [strike] with prejudice a [cause of action], or part of a [cause of action], if:

(1) the moving party establishes under Section 2(b) that this [act] applies;

(2) the responding party fails to establish under Section 2(c) that this [act] does not apply; and

(3) either:

(A) the responding party fails to establish a prima facie case as to each essential element of the [cause of action]; or

(B) the moving party establishes that:

(i) the responding party failed to state a [cause of action] upon which relief can be granted; or

(ii) there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on the [cause of action] or part of the [cause of action].

(b) A voluntary [dismissal] [nonsuit] without prejudice of a responding party's [cause of action], or part of a [cause of action], that is the subject of a motion under Section 3 does not affect a moving party's right to obtain a ruling on the motion and seek costs, attorney's fees, and expenses under Section 10.

(c) A voluntary [dismissal] [nonsuit] with prejudice of a responding party's [cause of action], or part of a [cause of action], that is the subject of a motion under Section 3 establishes for the purpose of Section 10 that the moving party prevailed on the motion.

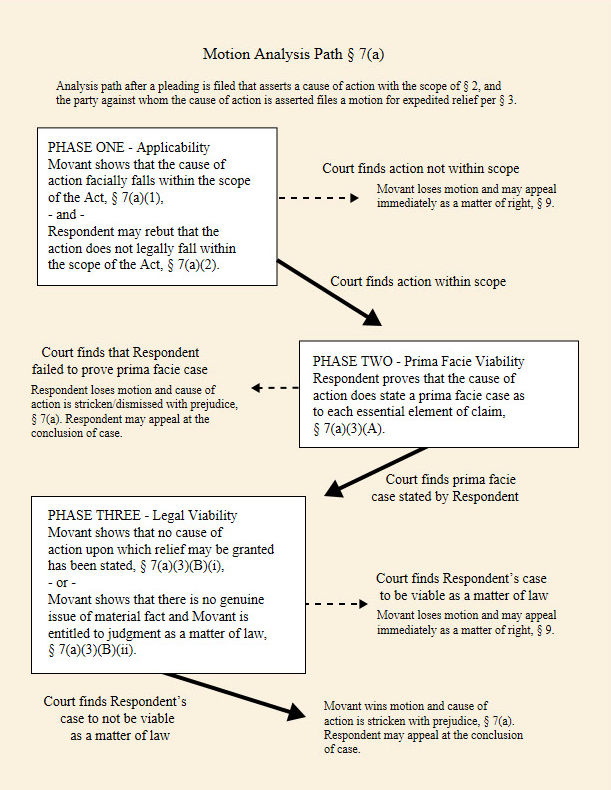

JayNote: Before we go into the analysis of this section below, please consider this chart. It is your friend.

SECTION 7. [DISMISSAL OF] [STRIKING] CAUSE OF ACTION IN WHOLE OR PART.

(With Commentary Interlineated)

(a) In ruling on a motion under Section 3, the court shall [dismiss] [strike] with prejudice a [cause of action], or part of a [cause of action], if:

§ 7 comment 1.

Section 7(a) recognizes that a court can strike or dismiss a part of a cause of action—for example, certain operative facts or theories of liability—and deny the motion as to other parts of the cause of action. E.g., Baral v. Schnitt, 376 P.3d 604, 615 (Cal. 2016) (holding that California's statute can be utilized to challenge all or only part of a single cause of action, because a single cause of action may rely on multiple instances of conduct, only some of which may be protected).

JayNote:

Section 7 is the engine room of UPEPA where the most critical working pieces of the Act are located. This is the section that tells a judge confronted with a UPEPA motion what analytical steps must be taken, and in what order, to resolve the motion. By like token, § 7 also tells the parties to a UPEPA motion exactly what they have to prove in their respective opening briefs, opposition briefs, and reply briefs ⸺ and the consequences if one party or another fails at any point in the process (and one must fail).

The drafting committee perhaps spent more time working on § 7(a) than any other provision and for good reason. Arguably, § 7(a) is the single most important provision to be found in the UPEPA, and all else merely supports it. A solid understanding of § 7(a) is therefore critical. There are four main issues raised in just this first sentence, so let's unpack it.

the court shall [dismiss] [strike]

This phrase, and particularly the use of the word "shall", makes clear that the court's action is mandatory, and not discretionary. Once the result is dictated by § 7(a), the court doesn't have a choice in the matter: The court must either strike the challenged cause of action or not strike the cause of action. The decision to strike is thus one of law, and later reviewable by the appellate court as such, and not of the use of the court's discretion.

Additionally, this phrase indicates what relief that the movant gets if the movant wins, which is that the challenged cause of action is either dismissed or stricken depending on local practice as decided by the state legislature. Very simply, if the movant wins the motion, then the challenged cause of action is gone from the lawsuit; it is no longer an issue to be litigated in any part.

with prejudice

The phrase "with prejudice" gives a UPEPA motion which is granted its finality in killing off the offending cause of action. The plaintiff cannot simply try to re-plead the cause of action, re-brand the cause of action as something else, or even bring the same cause of action in a completely different lawsuit, because the cause of action becomes completely and irrevocably dead (unless, of course, there is a successful appeal of the ruling on the motion).

a [cause of action]

It is this phrase which defines the target that a special motion is aimed at, which is a particular cause of action. A movant who files a special motion cannot seek to strike at the plaintiff's complaint generally, but must instead limit the special motion to only that cause of action, or those causes of action if there are several, that fall within the scope of a UPEPA special motion. To the extent that a special motion seeks to also take out other causes of action that are not within that scope, the special motion should be ignored. This phrase would also prevent a special motion from being used to try to strike something which is not a cause of action, such as factual allegations or prayers for damages or remedies, unless they are part and parcel of a cause of action which should be stricken.

Note also that the phase "cause of action" is bracketed in the UPEPA, which reflects that particular jurisdictions may use a different term of similar meaning, and the brackets essentially tell the legislature to instead insert in that place the alternative terminology.

or part of a [cause of action]

It may be that a particular cause of action is only partially subject to being stricken, and in such a case the court should carefully and surgically excise only the offending parts of the cause of action, and leave the rest untouched. This is further made clear by Comment 1 to § 7: "Section 7(a) recognizes that a court can strike or dismiss a part of a cause of action—for example, certain operative facts or theories of liability—and deny the motion as to other parts of the cause of action, e.g., Baral v. Schnitt, 376 P.3d 604, 615 (Cal. 2016) (holding that California's statute can be utilized to challenge all or only part of a single cause of action, because a single cause of action may rely on multiple instances of conduct, only some of which may be protected)."

How all this is accomplished is by an analysis to be conducted by the court in what amounts to three phases in which the following questions of law are to be resolved:

Phase One: Can the moving party establish that the offending cause of action (or part of a cause of action) fall within the scope of UPEPA as delineated in § 2?

Phase Two: Can the responding party establish a prima facie case which should survive the special motion even if it is within the scope of § 2?

Phase Three: Can the movant establish that, even if the responding party can make out a prima facie case that survives being within the scope of § 2, the movant should still prevail on the cause of action as a matter of law?

Each of these three phases will be discussed in depth below.

(1) the moving party establishes under Section 2(b) that this [act] applies;

§ 7 comment 2 ¶ 1.

Section 7(a)(1) establishes "Phase One" of the motion's procedure—applicability.

In this phase, the party filing the motion has the burden to establish the Act applies for one of the reasons identified in Section 2(b).

To use the Act, a movant need not prove that the responding party has violated a constitutional right—only that the responding party's suit arises from the movant's constitutionally protected activity. THOMAS R. BURKE, ANTI-SLAPP LITIGATION § 3.2 (2019).

Nor does the moving party need to show that the responding party intended to chill constitutional activities (motivation is irrelevant to the phase-one analysis) or prove that the responding party actually chilled the movant's protected activities. Id.

But "[t]he mere fact that an action was filed after protected activity took place does not mean the action arose from that activity for the purposes of the anti-SLAPP statute. Moreover, that a cause of action arguably may have been 'triggered' by protected activity does not entail it [as] one arising from such." Navellier v. Sletten, 52 P.3d 695, 708-09 (Cal. 2002).

Rather, the Act is available to a moving party if the conduct underlying the cause of action was "itself" an "act in furtherance" of the party's exercise of First Amendment rights on a matter of public concern. See City of Cotati v. Cashman, 52 P.3d 695, 701 (2002).

The moving party meets this burden by demonstrating two things: first, that it engaged in conduct that fits one of the three categories spelled out in Section 2(b); and second, that the moved-upon cause of action is premised on that conduct. See id.

In short, the Act's "definitional focus is not the form of the [non-movant's] cause of action but, rather, the [movant's] activity that gives rise to his or her asserted liability—and whether that activity constitutes protected speech or petitioning." Navellier, 52 P.3d at 711.

§ 7 comment 2 ¶ 2.

In many instances, the moving party will be able to carry its burden simply by using the responding party's pleadings. See Hersh v. Tatum, 526 S.W.3d 462, 467 (Tex. 2017) ("When it is clear from the plaintiff's pleadings that the action is covered by the Act, the defendant need show no more.").

As pointed out in Comment 2 to Section 6, a party is always free to use an opposing party's pleadings as stipulations and admissions, and when the Complaint spells out the cause of action and the activity underlying that cause of action, the moving party will be able to satisfy its burden rather easily.

For example, if a defendant is sued by a public official for defamation, and the Complaint identifies the allegedly defamatory statement made by the defendant, then the defendant should need to do no more than attach the Complaint as an exhibit to its motion—the Complaint itself would clearly demonstrate that the defendant is being sued for speaking out about a public official (undoubtedly a matter of public concern).

§ 7 comment 2 ¶ 3.

In other instances, the moving party will have to attach evidence to its motion to establish that the cause of action is based on the exercise of protected activity.

That's because a creative plaintiff can disguise what is actually a SLAPP as a "garden variety" tort action.

"Thus, a court must look past how the plaintiff characterizes the defendant's conduct to determine, based on evidence presented, whether the plaintiff's claims are based on protected speech or conduct." BURKE, supra at § 3.4.

§ 7 comment 2 ¶ 4.

But the fact that the movant's burden must be carried with evidence—whether that be the responding party's pleadings or evidence the movant presents—does not mean the inquiry is a factual one.

On the contrary, the motion is legal in nature, and the burden is likewise legal.

§ 7 comment 2 ¶ 5.

Thus, the court should not impose a factual burden on the moving party — like "preponderance of the evidence" or "clear and convincing evidence" — typically seen in fact-finding inquiries.

§ 7 comment 2 ¶ 6.

Rather, like other legal rulings, the court should simply make a determination, based on the evidence produced by the moving party, whether a cause of action brought against the moving party is based on its (1) communication in a legislative, executive, judicial, administrative, or other governmental proceeding; (2) communication on an issue under consideration or review in a legislative, executive, judicial, administrative, or other governmental proceeding; or (3) exercise of the right of freedom of speech or of the press, the right to assemble or petition, or the right of association, on a matter of public concern.

It should do so without weighing the parties' evidence against each other, but instead by determining whether the evidence put forth by the movant establishes the legal standard.

If the moving party fails to prove the Act applies, the motion must be denied.

JayNote:

THE PHASE ONE ANALYSIS: IS THE CAUSE OF ACTION WITHIN THE SCOPE OF UPEPA?

The first question before the court is whether UPEPA even applies at all, meaning whether the offending cause of action falls within the scope of the Act as described in § 2(b). If it does, then the court will have to analyze further; but if not, the motion fails at that point. To this end, § 7(a)(1) describes the burden of the moving party in establishing that the cause of action falls within §2 (b), and § 7(a)(2) describes the burden on the responding part in establishing that the cause of action falls into one of the exceptions of § 2(c).

Subpart (1) of § 7(a) sets forth the what happens on the opening salvo of a special motion, which is the opening brief filed by the movant. There is a lot to be found in these 10 words, so let's unpack them as well.

the moving party establishes

The phrase "the moving party establishes" accomplishes at least two things. First, it requires the movant to file the opening brief and make its case why the special motion should be granted. Second, the term "establishes" places the burden of proof squarely movant at this stage of the analysis. Exactly what the movant must show is set forth in the following clause.

under Section 2(b) that this [act] applies

It will be recalled that § 2(b) describes the scope of UPEPA, i.e., the speech or conduct which is protected by the Act. This clause requires the movant to demonstrate to the court that the offending cause of action falls somewhere within the description of § 2(b). If the movant succeeds, then the court proceeds to the next step of the analysis; but if the movant fails, then the special motion has failed right there and right then, and there is no reason for the analysis to proceed further.

This analysis is one of law: The court should look at the offending cause of action as plead by the plaintiff (respondent), and determine whether that cause of action in any part satisfies the description of § 2(b). See Comment 2 § 7(a) ¶ 2, "In many instances, the moving party will be able to carry its burden simply by using the responding party's pleadings." However, this does not prevent the movant from attaching evidence to its opening brief and arguing facts which put the cause of action into context so that the court can see more clearly exactly what it is that the offending cause of action is meant to address. Such will be the case where the plaintiff has plead the cause of action vaguely so that it is difficult to determine exactly what speech or conduct it is aimed at, or not. The movant is not required to make such proof — if it is merely arguable that the offending cause of action violates protected speech or conduct then the movant has still met its burden under § 7(a)(1) — but the movant is not prohibited from doing so either. This is made clear by Comment 2 to § 7(a)(1) ¶ 1:

In this phase, the party filing the motion has the burden to establish the Act applies for one of the reasons identified in Section 2(b). To use the Act, a movant need not prove that the responding party has violated a constitutional right — only that the responding party's suit arises from the movant's constitutionally protected activity. Thomas R. Burke, Anti-SLAPP Litigation § 3.2 (2019). Nor does the moving party need to show that the responding party intended to chill constitutional activities (motivation is irrelevant to the phase-one analysis) or prove that the responding party actually chilled the movant's protected activities. Id."

Thus, at the § 7(a)(1) opening brief stage of the special motion, the movant is only required to prove that the offending cause of action falls within the scope of the Act under § 2(b). The movant could properly stop right there, and not say anything further, and thus pass the burden to the respondent. In practice, however, the movant will probably use the opening brief as an opportunity to attempt to pre-empt the respondent's opposition brief arguments. The reason the movant should want to engage in such pre-emptive argument is the very practical one that the movant's opening brief is the largest brief that the movant will get to file, it normally only takes a couple of pages to establish that the offending cause of action falls within the scope as described by § 2(b), and thus the movant would otherwise be left wasting the unused pages — not knowing if the movant will have sufficient pages in its reply brief to address all of the respondent's opposition brief arguments. By like token, pre-emptively briefing the respondent's arguments will cause the respondent to use up its limited briefing pages to address the movant's pre-emptive arguments. So, as a tactical matter, pre-emptively addressing the respondent's anticipated arguments in the movant's opening brief will usually be done.

(2) the responding party fails to establish under Section 2(c) that this [act] does not apply; and

§ 7 comment 3.

Section 7(a)(2) is also part of "Phase One" of the motion's procedure.

Even if the Act applies for one of the reasons identified in Section 2(b), the Act may nevertheless not apply if the party against whom the motion is filed can establish the applicability of an exemption identified in Section 2(c).

A party seeking to establish the applicability of an exemption bears the burden of proof on that exemption.

Like establishing applicability under Section 2(b), the burden to establish non-applicability under Section 2(c) is legal, and not factual.

The responding party may use the moving party's motion, or affidavits or any other evidence admissible in a summary- judgment proceeding, to carry its burden.

And like the Section 2(b) analysis, the court should decide whether the cause of action is exempt from the act without weighing the evidence against that of the moving party, but instead by determining whether the evidence produced by the responding party establishes the applicability of an exemption.

If the responding party so establishes, the motion must be denied.

If the moving party proves the Act applies and the responding party cannot establish the applicability of an exemption, the court moves to "Phase Two" of the motion's procedure.

JayNote:

Like most motions, a special motion to strike can be thought of in tennis terms, in the sense that the parties' respective burdens shift as the ball passes back and forth over the net. The movant's opening brief is its serve. Once the serve is made, the responding party has the opportunity to prove that the serve was unsuccessful: It either hit the net or failed or landed outside the boundaries of the service box. Section 7(a)(2) basically works the same way.

the responding party fails to establish

Once the movant in its opening brief met its burden as to § 7(a)(1), then the burden passes to the respondent in its opposition brief to establish the following.

"under Section 2(c) that this [act] does not apply"

The respondent here must successfully argue that despite the offending cause of action falling within the scope of the Act as stated in § 2(b), the cause of action falls into one of the exceptions to scope as found in § 2(c), i.e., arising by or against a governmental entity in certain circumstances or from the sale or leasing of goods or services.

Comment 3 to § 7(a)(2) importantly notes:

"Like establishing applicability under Section 2(b), the burden to establish non-applicability under Section 2(c) is legal, and not factual. The responding party may use the moving party's motion, or affidavits or any other evidence admissible in a summary-judgment proceeding, to carry its burden. And like the Section 2(b) analysis, the court should decide whether the cause of action is exempt from the act without weighing the evidence against that of the moving party, but instead by determining whether the evidence produced by the responding party establishes the applicability of an exemption."

This concludes the Phase One analysis: By this point, the court should have determined whether, as a matter of law, the offending cause of action falls with the scope of § 2(b), and without falling into an exception under § 2(c). Assuming that it does, we then continue on to Phase Two.

(3) either:

(A) the responding party fails to establish a prima facie case as to each essential element of the [cause of action]; or

§ 7 comment 4 ¶ 1.

Section 7(a)(3)(A) establishes "Phase Two" of the motion's procedure — prima-facie viability.

Anti-SLAPP laws "do not insulate defendants from any liability for claims arising from protected rights of petition or speech.

[They] only provide[] a procedure for weeding out, at an early stage, meritless claims arising from protected activity." Sweetwater Union High Sch. Dist. v. Gilbane Bldg. Co., 434 P.3d 1152, 1157 (Cal. 2019) (emphasis original) (citations omitted).

Phase Two (as well as Phase Three) is where that "weeding out" occurs.

§ 7 comment 4 ¶ 2.

In this phase, the party against whom the motion is filed has the burden to show its case has merit by establishing a prima-facie case as to each essential element of the cause of action being challenged by the motion. See Baral v. Schnitt, 376 P.3d 604, 613 (Cal. 2016) (holding that a responding party cannot prevail on an anti-SLAPP motion by establishing a prima-facie case on any one part of a cause of action).

The moving party has no burden in this phase.

"Prima facie" means evidence sufficient as a matter of law to establish a given fact if it is not rebutted or contradicted. Dallas Morning News, Inc. v. Hall, 579 S.W.3d 370, 376-77 (Tex. 2019) (prima-facie evidence "is 'the minimum quantum of evidence necessary to support a rational inference that the allegation of fact is true'"); Wilson v. Parker, Covert & Chidester, 50 P.3d 733, 739 (Cal. 2002) ("[T]he plaintiff must demonstrate that the complaint is [ ] supported by a sufficient prima-facie showing of facts to sustain a favorable judgment if the evidence submitted by the plaintiff is credited.").

§ 7 comment 4 ¶ 3.

Precisely how the responding party carries its burden to establish a prima-facie case "will vary from case to case, depending on the nature of the complaint and the thrust of the motion." Baral, 376 P.3d at 614.

But the responding party should be afforded "a certain degree of leeway" in carrying its burden "due to 'the early stage at which the motion is brought and heard and the limited opportunity to conduct discovery.'" Integrated Healthcare Holdings, Inc. v. Fitzgibbons, 44 Cal. Rptr. 3d 517, 529 (2006) (citations omitted).

California courts have "repeatedly described the anti-SLAPP procedure as operating like an early summary judgment motion." THOMAS R. BURKE, ANTI-SLAPP LITIGATION § 5.2 (2019).

"[A] plaintiff's burden as to the second prong of the anti-SLAPP test is akin to that of a party opposing a motion for summary judgment." Yu v. Signet Bank/Virginia, 126 Cal. Rptr. 2d 516, 530 (Cal. Ct. App. 2002) (disapproved of on other grounds by Newport Harbor Ventures, LLC v. Morris Cerullo World Evangelism, 413 P.3d 650 (Cal. 2018)).

§ 7 comment 4 ¶ 4.

Accordingly, all a responding party must do to satisfy its burden under Phase Two is produce evidence that, if believed, would satisfy each element of the challenged cause of action.

A court may not weigh that evidence, but rather must take it as true and determine whether it meets the elements of the moved-upon cause of action. Sweetwater Union High Sch. Dist., 434 P.3d at 1157.

If the responding party cannot establish a prima-facie case, then the motion must be granted and the cause of action (or portion of the cause of action) must be stricken or dismissed.

If the responding party does establish a prima-facie case, then (and only then) the court moves to "Phase Three" of the motion's procedure.

JayNote:

PHASE TWO: CAN THE RESPONDENT MAKE OUT A PRIMA FACIE CASE?

That the offending cause of action falls within the scope of § 2(b) does not ipso facto mean that the cause of action should be stricken, only that the court should inquire further to determine whether the cause of action is nonetheless legally viable, i.e., it could withstand a motion for summary judgment (recalling that a special motion to strike is sometimes referred to, and not wholly inaccurately, as an "early summary judgment motion".)

The Phase Two Analysis is set out in § 7(a)(3)(A) and (B)(i), with the Phase Three Analysis being set out in (B)(ii).

Subsection 7(a)(3)(A) imposes the requirement upon the respondent to demonstrate that, even after all constitutional and other protections for free speech and conduct are taken into account, the respondent can still make out a viable cause of action that it has a chance of winning on at trial.

For example, assume that a cause of action for defamation is filed against the respondent, and the movant files a special motion to strike on the basis that the respondent's cause of action falls within the boundaries of constitutionally-protected speech. The respondent then files an opposition brief which shows that the nature of the cause of action as plead in the complaint is such that the law would allow the defamation suit to proceed anyway. In that event, the respondent would have met its Phase Two burden.

Thus, as Comment 4 to § 7 points out: "Anti-SLAPP laws 'do not insulate defendants from any liability for claims arising from protected rights of petition or speech. [They] only provide[] a procedure for weeding out, at an early stage, meritless claims arising from protected activity.' Sweetwater Union High Sch. Dist. v. Gilbane Bldg. Co., 434 P.3d 1152, 1157 (Cal. 2019) (emphasis original) (citations omitted)." Let's now dive into the clause of § 7(a)(3)(A).

the responding party fails to establish a prima facie case

The import of this clause is that the burden is upon the respondent to show that the offending cause of action is legally viable, i.e., states a prime facie case against the movant that would survive a motion for summary judgment.

What this means for the respondent in practice is that if the respondent is going to plead a cause of action in an area of constitutionally-protected speech or conduct, the respondent had better carefully craft the pleading so that a prima facie cause of action is stated. But there is another important ramification as well: The respondent must submit with its opposition brief at least sufficient evidence to minimally prove-up its case as if it were a motion for summary judgment. Here, Comment 4 to §7 (a)(3)(A) elucidates:

"'Prima facie' means evidence sufficient as a matter of law to establish a given fact if it is not rebutted or contradicted. Dallas Morning News, Inc. v. Hall, 579 S.W.3d 370, 376-77 (Tex. 2019) (prima-facie evidence 'is 'the minimum quantum of evidence necessary to support a rational inference that the allegation of fact is true' '); Wilson v. Parker, Covert & Chidester, 50 P.3d 733, 739 (Cal. 2002) ('[T]he plaintiff must demonstrate that the complaint is [ ] supported by a sufficient prima-facie showing of facts to sustain a favorable judgment if the evidence submitted by the plaintiff is credited.')."

Note that the court is not to weigh the evidence submitted by the respondent ⸺ the weighing of evidence on a special motion is not authorized and inappropriate ⸺but only to determine (again, as if on a motion for summary judgment) whether such minimal evidence has been presented by the respondent that the case can go forward to trial.

Let us now move on to the next clause in § 7(a)(3)(A).

as to each essential element of the [cause of action]

The meaning of this clause is obvious: The respondent must prove that at least minimal evidence exists to support each and every required element of the cause of action. Otherwise stated, the respondent must bowl a perfect strike with the evidence that it presents to the court, but if even a single pin is left standing then the special motion should be granted. Having said this, Comment 4 notes that because the court is essentially applying an end-game summary judgment standard to a proceeding which occurs at the very outset of the litigation, and before the respondent has had the opportunity to conduct discovery, the court should probably grant some leeway to the respondent in satisfying its burden on this point, i.e., perhaps slightly lean in the respondent's favor in a way that would not otherwise occur on a summary judgment motion after the close of discovery.

The respondent is now the only player, however, in a Phase Two Analysis, since the movant can also weigh in on whether the respondent can show that it has a legally viable case. That then brings us to § 7(a)(3)(B)(i).

(B) the moving party establishes that:

(i) the responding party failed to state a [cause of action] upon which relief can be granted; or

(ii) there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on the [cause of action] or part of the [cause of action].

§ 7 comment 5 ¶ 1.

Section 7(a)(3)(B) establishes "Phase Three" of the motion's procedure—legal viability.

Even if a responding party makes a prima-facie showing under Section 7(a)(3)(A), the moving party may still prevail if it shows that the responding party failed to state a cause of action upon which relief can be granted or that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law—in other words, that the cause of action is not legally sound.

In this phase, the burden shifts back to the moving party.

If the moving party makes a showing under Section 7(a)(3)(B), then the motion must be granted and the cause of action (or portion of the cause of action) must be stricken or dismissed.

If the moving party does not make such a showing—and the responding party successfully established a prima-facie case in "Phase Two"—then the motion must be denied.

§ 7 comment 5 ¶ 2.

For example, a plaintiff desiring to build a "big box" store sues a defendant for tortious interference based on the defendant's efforts to organize a public campaign adverse to the plaintiff.

The defendant moves to dismiss under the Act and establishes that the suit targets her First Amendment activity on a matter of public concern.

Thus, the motion moves to Phase Two. In that phase, the plaintiff is able to establish a prima-facie case on each essential element of its tortious interference cause of action.

Thus, the motion moves to Phase Three.

But in that final phase, the defendant shows that the claim is barred by limitations.

In such an instance, the court must grant the motion, because the defendant showed itself to be entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

§ 7 comment 5 ¶ 3.

Although Phase Three uses traditional summary judgment and Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6) language, it does not serve as a replacement for those vehicles.

On the contrary, summary judgment and other dismissal mechanisms remain options for defendants who cannot establish that they have been sued for protected activity.

In other words, to get to Phase Three—and be entitled to the Act's sanctions under Section 10—a movant must first prevail under Phase One by showing the Act's applicability.

But by employing a legal-viability standard, the Act recognizes that a SLAPP plaintiff can just as easily harass a defendant with a legally nonviable claim as it can with a factually nonviable one.

JayNote:

In our ongoing tennis match, when the respondent proves that it has a legally viable cause of action this has the effect of the respondent knocking the ball back over the net and onto the movant's side of the court. The burden (and opportunity) then passes to the movant to win the point. The movant can do so that by pointing out that no matter what the respondent has plead for a cause of action, and no matter what proof the respondent has shown to support it, the respondent still cannot demonstrate a legally viable cause of action. The movant's shot, whatever it is, usually will be found in its reply brief (although, as noted, a smart movant will usually anticipate the respondent's argument and pre-empt those arguments and make its attack on the respondent's prima facie case in its opening brief where it has the luxury of additional pages to do so).

The movant's attack here is one or both of two ways: Either the respondent's cause of action fails to adequately plead as a matter of law all of the required elements of the offending cause of action, or that the respondent's proof of some element has failed.

For example, say the respondent files a cause of action that says that the movant defamed the respondent in a statement made on the Sammy Maudlin Show, and submits an affidavit which says that on a particular date the movant appeared on that show and suggested that the respondent is a securities fraudster, thus satisfying the element of defamation that a false statement purporting to be fact has been made. The movant, however, proves to the court that the respondent was in fact convicted of securities fraud some years previously ⸺ and which the respondent cannot rebut. Thus, the movant's statement was not false, and the movant has proven that the respondent cannot make out a legally viable cause of action for defamation based on that statement.

If the respondent has survived the Phase Two Analysis by showing that a prima facie cause of action has been plead and there is at least minimal evidence to support it (and the movant cannot rebut this), then the final analysis to be conducted by the court is the Phase Three Analysis of whether the movant will ultimately prevail anyway.

PHASE THREE ANALYSIS: WILL THE MOVANT PREVAIL ANYWAY?

In the Phase Three Analysis, the court considers whether there is particular evidence (and a lack of rebutting evidence on the part of the respondent) which leads to the conclusion that the movant will ultimately prevail on summary judgment anyway, even if the respondent can now make out a prima facie cause of action and support it with at least minimal evidence. This is what § 7(a)(B)(ii) is all about, and it will most often come in the form of an affirmative defense asserted by the movant.

For example, the respondent sues the movant for defamation. The movant files a special motion to strike. The respondent demonstrates that it has plead and can prove a legally viable cause of action as to each element of defamation, and the movant lacks the evidence to negate that proof. However, the movant can prove that the defamatory statement took place outside the applicable Statute of Limitations period for defamation, and so the respondent's cause of action fails anyway.

If the movant can prove a reason why the movant will win on summary judgment anyway, then there is no point in going forward any further with the litigation on that cause of action and it will be stricken. By like token, if the respondent can come forward with minimal evidence such that the court could not grant summary judgment on the issue, then the special motion will be denied.

Now let's look at each of the clauses in § 7(a)(3)(B).

the moving party establishes that there is

Back our tennis ball analogy, the ball is in the movant's court and the burden is thus on the movant to establish its defense.

"no genuine issue as to any material fact"

The phrase "no genuine issue as to any material fact" is of course the summary judgment standard, i.e., the court does not weigh evidence but merely determines whether sufficient evidence exists such that the issued could be trial. In the § 7(a)(3)(B) context, this would mean that all the relevant evidence as to the issue in question (such as an affirmative defense) supports the movant's position and there is no significant or at least minimally-credible evidence to the contrary.

and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on the [cause of action] or part of the [cause of action].

This purpose of this clause is to make clear that the movant is winning as a matter of law and not of fact, and the court is not to engage in a weighing of facts. Comment 5 to § 7(a)(3)(B) notes the purpose of this language: "But by employing a legal-viability standard, the Act recognizes that a SLAPP plaintiff can just as easily harass a defendant with a legally nonviable claim as it can with a factually nonviable one."

That ends the Three Phase Analysis of § 7(a), after which the court has either granted the special motion and stricken the offending cause of action (or part thereof), or it has denied the motion.

(b) A voluntary [dismissal] [nonsuit] without prejudice of a responding party's [cause of action], or part of a [cause of action], that is the subject of a motion under Section 3 does not affect a moving party's right to obtain a ruling on the motion and seek costs, attorney's fees, and expenses under Section 10.

JayNote:

We now turn to the remaining subsections of § 7 which deal with what happens when the respondent simply dismisses the offending cause of action prior to the special motion to strike being heard by the court. Subsection 7(b) manages a dismissal by the respondent "without prejudice" — which means that the respondent could simply re-file the cause of action later if it chose — while subsection 7(c) controls when the respondent has dismissed "with prejudice" so that the cause of action is forever dead and cannot thereafter be raised again.

A plaintiff may dismiss a cause of action voluntarily, and do so "without prejudice" which effectively reserves the plaintiff's ability to raise that cause of action at a later date, whether by an amendment to the existing complaint or (usually) by bringing a separate and new lawsuit. Where the plaintiff (respondent) has done so before the special motion to strike has been heard, the puts the movant into a situation where the movant has fully briefed the special motion, but there is now no cause of action to be stricken, and yet the axe of the possibility that the offending cause of action might later be brought again will hover over the movant's head (and thus potentially continue to intimidate the movant and chill the movant's exercise of free speech and conduct. As Comment 7 to § 7(b) notes: "Section 7(b) protects a moving party from the gamesmanship of a responding party who dismisses a cause of action after the filing of a motion, only to refile the offending cause of action after the motion is rendered moot by the claim's dismissal."

Subsection 7(b) addresses this precise situation, and allows the movant (if the movant chooses) to go forward with the special motion to strike and obtain a final determination on the offending cause of action nonetheless. If the movant's special motion is successful, then the cause of action is stricken and no longer poses a threat to the movant, and additionally the movant can seek costs, attorney's fees and expenses in connection with the special motion.

In effect, for purposes of the special motion and the effects thereafter, the effect of a dismissal without prejudice is practically the same as if that dismissal never happened ⸺ although in particular and unusual cases, a dismissal without prejudice might in some way towards the mitigation of the attorney's fees to be assessed against the respondent.

(c) A voluntary [dismissal] [nonsuit] with prejudice of a responding party's [cause of action], or part of a [cause of action], that is the subject of a motion under Section 3 establishes for the purpose of Section 10 that the moving party prevailed on the motion.

§ 7 comment 6.

Sections 7(b) and (c) recognize that a party may desire to dismiss or nonsuit a cause of action after a motion is filed in order to avoid the sanctions that accompany a dismissal under Section 10.

Both sections serve to maintain the moving party's ability to seek attorney's fees and costs—even though the offending cause of action has been dismissed—because the filing of a motion under the Act is costly, and many plaintiffs refuse to voluntarily dismiss their claims until a motion has been filed.

But a prudent moving party should take efforts to inform opposing parties that it intends to file a motion under the Act, so as to give them an opportunity to voluntarily dismiss offending claims before a motion is filed.

Courts may take a moving party's failure to do so into account when calculating the reasonableness of the moving party's attorney's fees.

§ 7 comment 7.

Section 7(b) protects a moving party from the gamesmanship of a responding party who dismisses a cause of action after the filing of a motion, only to refile the offending cause of action after the motion is rendered moot by the claim's dismissal.

§ 7 comment 8.

Once a motion has been filed, a voluntary dismissal or nonsuit of the responding party's cause of action does not deprive the court of jurisdiction.

§ 7 comment 9.

State law should dictate the effect of a dismissal of only part of a cause of action.

JayNote:

Section 7(c) deals with the situation where, after the special motion was filed, the responding party has dismissed the offending cause of action with prejudice. Where this happens, § 7(c) simply treats the special motion to strike as if has been conceded by the responding party and the special motion is granted by the court.

This situation will most often arise where the respondent has unintentionally and in error plead a cause of action that impinges upon the movant's protected speech or conduct, and by dismissing the offending cause of action (or part thereof) the respondent seeks to limit the attorney's fees, costs and expenses that would be incurred by the movant in prosecuting the special motion.

Of all the discussion about § 7 within the Drafting Committee, probably no topic took up anywhere as much time as that of how to treat the so-called "innocent violator", i.e., a respondent that has unknowingly filed a cause of action that violates the movant's protected speech or conduct. In this discussion, one of the most important things was that the Drafting Committee didn't want to get into the business of attempting to measure the respondent's intent, since attempting to determine the respondent's intent would generate significant litigation all its own which would then defeat the special motion's purpose of a quick and efficient vehicle to weed out bad causes of action from the beginning. Where the Drafting Committee ended up is embodied in § 7(b), which allows an "innocent violator" to essentially cut its losses by dismissing the offending cause of action with prejudice.

There was also considerable discussion amongst the Drafting Committee as to whether the movant should first be required to give the respondent some warning that a special motion to strike would be filed unless the respondent voluntarily dismissed the offending cause of action. Indeed, with a sizeable percentage of special motions to strike being brought for relatively benign technical violations of the movant's protected speech or conduct, this sort of warning made some sense. However, this idea was nixed for three reasons: First, there was no desire to create the potential for even more litigation over the adequacy of the notice given by the movant; second, no more work should be placed upon the movant in the case of an intentional violator; and, third, plaintiffs who are drafting pleadings in an area that is close to protected speech and conduct should simply exercise additional care.

While nonbinding, and ultimately not adopted by the Drafting Committee, Comment 6 to § 7 suggests that "a prudent moving party should take efforts to inform opposing parties that it intends to file a motion under the Act, so as to give them an opportunity to voluntarily dismiss offending claims before a motion is filed. Courts may take a moving party's failure to do so into account when calculating the reasonableness of the moving party's attorney's fees."

Where the respondent has dismissed the offending cause of action with prejudice, the movant is at that point immediately determined to have prevailed on the special motion to strike without any further action of the court. This leaves the movant in the position of having to then establish its right to the attorney's fees, costs and expenses incurred in connection with the special motion, which the movant may do by way of either a new motion to tax such fees, costs and expenses. Here, Comment 8 to § 7 importantly states notes that "Once a motion has been filed, a voluntary dismissal or nonsuit of the responding party's cause of action does not deprive the court of jurisdiction."

RULING AND ORDER ARTICLES

- 2021.08.09 ... The Uniform Public Expression Protection Act: Analysis And Dismissal

- 2021.03.15 ... The Uniform Public Expression Protection Act: The Three-Phase Analysis

DISMISSAL/STRIKING OPINIONS